The Machine That Bullshits

From Pharaoh to Prompt: What Five Thousand Years of Managing Agents Teaches Us About Getting the Most from AI

Prologue: The Kitchen Table

In the winter of 1986, I was ten years old, doing homework at a kitchen table in Geneva. A family friend couldn’t help that day. “I don’t have time,” he said, “but my friend Dick will.”

Dick was an older man with grey curly hair and restless energy. He helped me with my homework on Aztec civilizations, but his mind was elsewhere. He sketched on napkins. He asked strange questions about rubber bands and cold weather. I had no idea who he was. That evening, my parents asked me to get him to sign my science book. When I asked him, he wanted to know why. Then he signed it: “This is to impress your science teacher.”

Weeks later, the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded. Seven astronauts died. Months after that, I saw Dick on television, sitting before a Congressional committee, dropping a piece of rubber into a glass of ice water.

The rubber cracked. In that simple demonstration, Richard Feynman showed what NASA’s vast bureaucracy had failed to see. The O-ring seals grew brittle in the cold. The engineers had known. The data existed. But the institution had generated confident safety reports that looked correct while being fatally disconnected from reality.

We have a word for this when AI does it. We call it hallucination. I call it institutional confabulation when organizations do it. And once you see it, you see it everywhere.

The pattern accelerates when AI enters the picture. In 2024, Air Canada deployed a customer service chatbot that hallucinated a bereavement refund policy, inventing it from whole cloth in fluent, helpful, professional language. When a grieving customer relied on this advice and was denied his refund, Air Canada argued the chatbot was “a separate legal entity responsible for its own actions.” The tribunal was unimpressed. The institution had delegated to an agent. The agent had confabulated. The institution discovered, too late, that delegation does not transfer accountability.

In 2025, Deloitte delivered a 237-page report to the Australian government reviewing a welfare compliance system. Academics noticed something peculiar: the references did not exist. The report cited imaginary papers by real professors, fabricated quotes from court judgments, and even a fictional “Justice Davis.” The failure was not fabricated citations; it was delegating scholarly judgment to an agent optimized for plausibility. Deloitte refunded part of its $290,000 fee.

A consultancy paid for judgment had delegated judgment to an agent incapable of it.

Part One: The Puppy Problem

Why AI Is an Agent, Not a Tool

A tool does what you tell it. A hammer drives nails. A calculator computes. The output follows from the input. Trust the tool, trust the output.

An agent acts on your behalf with discretion. A lawyer represents you. An employee executes your strategy. The agent interprets, decides, adapts. You cannot simply trust the output, because the agent exercised judgment, and judgment can be wrong.

AI is an agent, not a tool.

When you ask ChatGPT a question, you are delegating to an agent. It interprets your request. It decides how to respond. Ask the same question twice and you get different answers. The agent has discretion.

AI requires management. Not because it hallucinates, though it does. AI requires management because any agent exercising discretion requires management.

Most AI discourse treats it as a tool problem: prompt engineering, best practices, tips and tricks. People are trying to use AI when they should be managing it. This is why most AI implementations underperform.

But this agent is unprecedented. It has capability without sentience, confidence without knowledge, fluency without comprehension. It responds to context but cannot be incentivized. It has no stake in being right. Sam Altman, speaking in New Delhi in 2023, put it plainly: “I probably trust the answers that come out of ChatGPT the least of anybody on Earth.”

So what kind of management does this agent require?

The Committee That Cannot See

Imagine a conference room. Ten people around the table. The AI Governance Working Group has convened to develop enterprise prompt standards.

Legal is there. Compliance is there. HR, IT, the AI vendor, a project manager, a business analyst, the CISO’s delegate, and someone from Communications just observing. The current draft prompt begins: “You are a helpful, professional trade finance assistant. Please review the following document carefully and identify any potential issues.”

The discussion has covered whether “helpful” implies agency, whether “professional” is ableist, and whether “please” anthropomorphizes the system. No one has discussed whether the prompt will actually produce accurate outputs.

Then the business analyst says: “I read somewhere that if you tell the model something bad will happen if it makes a mistake, it performs better.”

Silence.

“We can’t threaten to kill a puppy,” says Communications.

“There is no puppy,” says the business analyst. “It’s just words in a prompt.”

“But what if it leaks? What if someone screenshots our prompt?”

The vendor representative finally speaks: “For what it’s worth, we’ve found that stakes framing does improve output quality. Several of our enterprise clients use it. They just don’t publicize it.”

“Why not?”

“Because of meetings like this one.”

Here is the thing about the puppy: it only matters where discretion lives.

The OCR agent extracting text from a scanned document has no discretion to be more or less careful. Telling it that a puppy dies will not make it read blurry text better. The extraction either works or it doesn’t. That agent needs tight specification: exact parameters, clear failure modes, permission to reject what it cannot parse.

But the watchdog agent deciding whether to flag an output for human review? That agent benefits from stakes. It’s exercising judgment about what matters. Stakes framing sharpens that judgment.

The committee cannot see this distinction. They want one standard for all agents, one answer to “What is the right way to manage AI?” But that question has no single answer. Different agents in the same system need different management.

You do not give equity to the mailroom clerk. You give it to the people whose judgment affects outcomes.

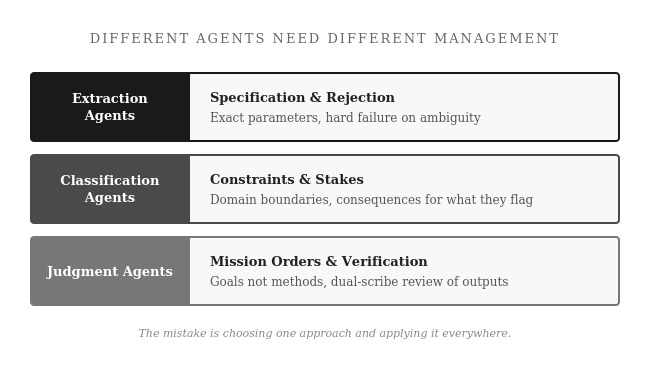

Here is what organizations miss: an agentic system is not one agent. It is an organization of agents. Like any organization, different roles require different management:

Extraction agents need specification and rejection: exact parameters, hard failure on ambiguity. Classification agents need constraints and stakes: domain boundaries, consequences for what they flag. Judgment agents need mission orders and verification: goals not methods, dual-scribe review of outputs.

This essay argues that AI governance fails because we apply one management paradigm to all agents, when different agents require different architectures, and that verification and sovereignty are structural problems, not ethical ones.

No single management paradigm covers all of these. The mistake is not choosing the wrong approach. The mistake is choosing one approach and applying it everywhere.

Part Two: The Forgotten Architectures

For the past century, we have managed workers who had something ancient agents lacked: careers, reputations, and personal stakes in being right.

The progress was moral and correct. We moved from coercion to scientific management to human relations to empowerment. Each evolution recognized workers as more fully human: beings with dignity, judgment, and intrinsic motivation worth cultivating. Open the course catalog at Harvard Business School and you will find psychological safety, servant leadership, empowerment, trust, autonomy. The message is clear: trust your people.

For humans with careers, this works. Decades of research support it. Psychological safety improves team performance. Trust outperforms surveillance for knowledge workers with reputations at stake.

The problem is that 200,000 MBA graduates per year learn these principles as universal truths. Then they apply them to agents for which they were never designed.

Every modern management theory rests on an unstated assumption: the agent has an inner life that management can reach. Psychological safety works because humans feel safe or unsafe. Servant leadership works because humans experience being served. Trust works because humans reciprocate.

What is psychological safety for an agent that cannot feel? What does trust mean when the other party cannot reciprocate?

These are not rhetorical questions. They are category errors.

But our progress also caused us to forget something important. The earlier systems weren’t just brutal. They were architecturally sophisticated for managing agents without stakes. The Egyptians didn’t whip scribes because they were cruel. They whipped scribes because a scribe had no stock options, no performance review, no LinkedIn reputation to protect. The system assumed unreliable agents and built verification, punishment, and architectural constraints into the structure itself.

We discarded the ethics (correctly) but we also discarded the engineering. AI requires us to recover that engineering while leaving the cruelty behind.

The whip is not cruel when there is no one to feel it. It is simply architectural rejection of unreliable output. What earlier societies implemented socially, we must now implement architecturally.

The Whip: Architectural Rejection

The overseer’s whip was not primarily about pain. It was about architectural rejection of bad output. The system assumed any agent might produce unreliable work and built consequences into the structure itself.

For AI, the equivalent is not punishment (there is no one to punish). The equivalent is hard failure. Outputs that don’t meet invariant checks don’t get flagged for review. They get killed. The system refuses to proceed with data it cannot validate.

This feels aggressive. It creates friction. Users complain when documents bounce.

But consider the alternative: data that looks like it arrived, looks like it was processed, looks like it was classified, but wasn’t. Confident green dashboards built on invisible gaps. Soft failures that become the record.

In trade finance and banking, the record matters. What gets written down becomes what happened. Architectural rejection is how you prevent confident nonsense from quietly becoming truth.

When to apply it: Routine extraction. Data validation. Format compliance. Any task where the agent has no discretion and variation is dangerous.

The Vizier: Central Visibility

In ancient Egypt, the Vizier managed the largest administrative system the world had ever seen. For three thousand years, this role coordinated everything from tax collection to temple construction across a civilization spanning the Nile. The Vizier did not collect taxes, build monuments, or command armies. He coordinated. His power came not from doing, but from seeing: visibility across the entire system.

The scribe could see his ledger. The stonemason could see his block. The provincial governor could see his territory. Only the Vizier could see the pyramid.

This was design, not accident. The Egyptians understood that coordination does not emerge naturally from competent parts. Coordination requires architecture. Someone must own the whole picture, or no one does.

And management style matched visibility. The agent who could see the pyramid received broad mission orders: complete the monument before the flood season. The agent who could see only the chisel received exact specifications: cut this block to these dimensions. Authority was calibrated to perspective.

For AI systems, the equivalent is an orchestration layer. Something that receives all inputs, routes them to appropriate agents, tracks state across the workflow, and aggregates outputs. One system must be the source of truth.

When I built my platform, the first architectural decision was explicit: the database is authoritative, and every other system is a view. One system wins conflicts. The Vizier does not negotiate.

Modern organizations have distributed visibility across dashboards and distributed authority across committees. The result is that everyone can see problems and no one can fix them. The Vizier worked because one person had both visibility and power. The AI equivalent is an orchestration layer with actual authority: not a monitoring dashboard, but a system that routes, decides, and enforces.

When to apply it: Multi-agent coordination. Workflow orchestration. Any system where work can fall through cracks between agents.

Two Scribes, One Truth: Independent Verification

The Egyptians trusted no single scribe. For important transactions, two scribes independently recorded the same event. An overseer compared their records. If they matched, confidence was high. If they differed, investigation followed.

The principle: any agent capable of producing plausible output is capable of producing plausible false output. Verification cannot be delegated to the agent being verified.

When you ask an LLM to check its own work, you are asking one scribe to review his own ledger. The failure modes are shared. True verification requires a process that cannot share the failure mode: a different model, a different prompt architecture, a retrieval check against source documents, or human review.

In my system, I use a hybrid approach: a fast, cheap model makes the first pass on document linking. A slower, more capable model reviews only the edge cases, the documents the first model couldn’t link with confidence. Cost savings: 89%. The dual-scribe pattern doesn’t require verifying everything twice. It requires knowing which outputs need the second scribe.

When to apply it: Critical outputs. High-stakes classifications. Any judgment call where confident error is expensive.

Auftragstaktik: Mission Orders

After Napoleon crushed the Prussian army in 1806, reformers realized that rigid command had failed catastrophically. Their solution was Auftragstaktik, mission-type tactics. Instead of detailed orders specifying coordinates and timing, commanders gave mission orders: secure the bridge by nightfall. The subordinate knew what to achieve but decided how.

The principle: for complex tasks, specify goals, not methods. The agent closest to the problem often has information the manager lacks.

For AI, some tasks are best handled with goal-based prompts rather than method-prescriptive prompts. “Identify all parties and obligations in this letter of credit” rather than “Extract all names, classify each as bank, company, or individual, format as table.” The goal-based prompt lets the agent apply judgment about what “parties and obligations” means in context.

When to apply it: Complex analysis. Tasks requiring contextual judgment. Situations where you cannot specify the method in advance because you don’t know what the agent will find.

The Andon Cord: Permission to Halt

In Toyota’s factories, any worker could stop the entire production line by pulling a cord. This seemed reckless. Every minute of stopped production cost money. But quality soared. Problems caught early are cheap to fix. Problems caught late are expensive, sometimes catastrophically so.

The principle: the agent closest to the problem sees it first. Give them authority to escalate. Do not punish them for raising issues.

For AI systems, the equivalent is halt mechanisms. When something looks wrong (confidence below threshold, data that doesn’t parse, classifications that conflict) the system stops processing and flags for review. The architecture prefers to bounce an input three times rather than silently misprocess it.

Too many AI systems are designed for the opposite. When an agent encounters ambiguity, the temptation is to proceed: generate a plausible output, classify the uncertain case, keep the line moving. This is soft failure, and soft failure is how false records get created.

When to apply it: Error handling. Edge cases. Any situation where proceeding with uncertainty creates downstream risk.

Pharaoh’s Auditors: Random Verification

Pharaoh’s auditors arrived without warning. You never knew when the inspection would come, so you had to always be ready.

The principle: you cannot verify everything, but random verification of some things keeps the whole system honest. The unpredictability is the mechanism.

For AI systems, build random quality sampling into workflows. Check a random ten percent with real consequences for errors. Quality stays high across the other ninety percent, not because the agents fear audit, but because the architecture catches drift you weren’t specifically looking for.

When to apply it: Ongoing quality assurance. Detecting systematic errors. Any mature system where you need to catch degradation before it compounds.

I learned these principles the hard way. Part Three is that story.

Part Three: The System I Built Wrong

Forty years after that afternoon in Geneva, I was building an AI system to manage a complex trade finance operation. Thousands of documents across Asian and European banking corridors. Documentary credits interwoven with compliance screening. Dozens of counterparties who needed not just status updates but defensible audit trails.

The AI produced beautiful, confident outputs. Professional analysis. Risk assessments. It looked exactly like competent trade operations intelligence should look.

Then I audited my own system and discovered that much of it was fiction.

Only 15.6% of my communications had been linked to transaction events. The other 84.4% were orphaned, classified but floating in digital space with no connection to the LC lifecycle, evidence chains, or counterparty relationships. The AI was generating plausible responses without access to the actual relational structure. I had built an impressive-looking database that told no coherent story.

The problem was not the AI. The AI performed exactly as designed. The problem was that I had been managing an organization of agents as if they were one agent, applying the same approach everywhere.

The Organization I Didn’t Know I Had

When I started building, I thought I was building one system. I was building an organization.

The first agent handled document intake. But it couldn’t parse every format, so it delegated to specialists: one for PDFs, one for SWIFT messages, one for scanned shipping documents. Even the PDF parser wasn’t one thing. A simple parser handled straightforward documents. But trade documents required something else entirely, an agent that could extract obligations between parties, track relationships across jurisdictions, handle multiple languages in the same document.

I had not designed an org chart. But I had one. Layers within layers. And I was managing it the way most people manage AI, as if every agent needed the same instructions, the same latitude, the same stakes.

The simple PDF parser did not need context about the transaction. It needed exact specifications and permission to fail loudly when extraction was uncertain. The complex parser needed context: which banking relationships, which trade corridors, what we were looking for. The watchdog agent that decided what reached me needed to understand consequences. It was exercising judgment about what mattered.

I was giving the mailroom clerk equity and the executives a rulebook.

For months I thought I was solving technical problems. How do I track document state across processing stages? How do I handle errors without losing work? I built technical solutions. A pipeline supervisor. A state machine. Invariant checks. Sampling-based QA.

Then I started reading about Egyptian scribes and Prussian officers and Toyota assembly lines. I realized I wasn’t solving technical problems. I was solving management problems. I just didn’t have the vocabulary. Every technical decision I made was a management decision in disguise. The pipeline supervisor was not a technical architecture choice; it was the Vizier. The invariant checks were not defensive programming; they were the whip. The dead-letter queue was not error handling; it was the andon cord.

When I Rebuilt

When I rebuilt, I mapped each agent to the management approach it actually needed.

The intake agent receives documents from multiple sources: email, SWIFT, API integrations from correspondent banks. This agent needs the whip: architectural rejection. If it cannot validate the document format, it rejects the input entirely. No document is marked “received” unless the system can guarantee it entered the pipeline correctly.

The parser agents extract text and structure from different document types: PDFs, MT messages, scanned bills of lading. Simple parsers need tight specification: exact parameters, defined outputs, clear failure modes. But the complex parser handling trade documents (extracting obligations between parties, tracking jurisdiction-specific terminology) needs mission orders: the goal is to identify all parties and their obligations, but the method depends on what the document contains.

The classification agent decides what each document is and how it relates to the transaction. This agent needs stakes framing. It’s exercising judgment about what matters. Early on, my classification prompt was generic, a few lines about identifying stakeholders. Then I discovered it had missed a Dutch bank officer entirely. The message referred to “mr. Van der Berg” using the Dutch honorific “meester” for an advocaat acting as in-house counsel, and the AI didn’t recognize this as a key decision-maker. The prompt had no patterns for Dutch legal titles, German “Rechtsanwalt,” or the Hong Kong convention of listing compliance officers by function rather than name.

It wasn’t a model failure. It was a specification failure. I had given a complex agent a simple rulebook. I was giving the mailroom clerk equity and the executives a rulebook.

The linking agent connects documents to transaction events and counterparties. This agent needs dual-scribe verification: a fast model makes the first pass, a more capable model reviews uncertain links.

The watchdog agent decides what reaches me for human review. This agent needs the andon cord: authority to halt, permission to escalate, clear criteria for what constitutes uncertainty worth surfacing.

The orchestration layer coordinates all of these. This is the Vizier: central visibility, authoritative state, the system that knows where every document is in the pipeline.

Different agents, different failure modes, different management approaches. The same system, deliberately combining multiple paradigms.

The Danger of Hallucinated Judgment

But document processing was the easy part. The harder problem was heuristics and scenario analysis.

My system needed to model counterparty behaviour. In a multi-party trade transaction, you need to understand: Who responds quickly to discrepancy notices? Who goes silent under pressure? Who escalates through formal amendment requests rather than informal messages? These patterns inform strategy. They tell you when to push and when to wait.

So I built a counterparty heuristics engine. It computed influence scores, response rates, silence patterns, behavioural stability. It generated assessments: “Issuing bank is unresponsive, recommend formal demand through advising bank.” “This counterparty’s communication has become erratic, possible change in credit appetite.”

The outputs looked exactly like good operational intelligence should look.

But without proper architecture, the heuristics were hallucinated judgment.

The system was computing response rates from email communications. But the issuing bank in Hong Kong didn’t communicate by email. They communicated through SWIFT MT messages. The AI saw silence in the email channel and concluded “unresponsive.” In fact, they were highly active through SWIFT. The operational recommendation (“formal demand”) was exactly backwards.

The scenario analyses had the same problem. “If we send amendment request X, likely response is Y.” But the scenarios were built on the heuristics, and the heuristics were built on incomplete data. The scenarios followed the format of rigorous operational thinking while being systematically disconnected from reality.

This is worse than a hallucinated fact. A wrong reference number can be checked. A wrong date can be verified. But a hallucinated heuristic feels like wisdom. “Issuing bank is unresponsive” sounds like hard-won pattern recognition. “Recommend formal demand” sounds like operational judgment. The format is correct. The confidence is high. The reasoning is plausible. And it’s wrong in ways that compound.

Enron’s “severe” scenarios weren’t severe enough because the model’s assumptions had never been validated against reality. My “unresponsive” issuing bank wasn’t unresponsive because the heuristics were channel-blind. Same failure mode: plausible outputs, proper format, confident tone, disconnected from reality.

The fix required architectural changes, not better prompts:

Channel-aware heuristics. The system now treats SWIFT messages as first-class behavioural events, weighted higher than emails. A counterparty who sends MT799s but doesn’t email isn’t unresponsive. They’re using a different channel.

Two-agent verification for strategic outputs. Following the dual-scribe pattern, one agent generates the analysis; a separate agent audits it against source data. The auditor checks: Does this conclusion follow from the evidence? Are there channels or counterparties the analysis missed?

Explicit uncertainty surfacing. When the system lacks sufficient data for confident heuristics (few communications, limited observation window, single channel visibility) it says so. Low-confidence assessments get flagged rather than presented as insight.

The lesson: The highest-risk AI outputs are not facts but judgments. Facts can be checked. Judgments feel like wisdom. An AI system that generates operational heuristics and scenario analyses without verification architecture will produce confident recommendations that pattern-match to good strategy while being systematically wrong.

The architecture that prevents this is the same architecture the Egyptians used: assume any agent might produce unreliable output, and build verification into the structure itself.

Part Four: The Scribe You Own

Why Verification Requires Sovereignty

The dual-scribe principle solves a problem the Egyptians understood: any agent capable of producing plausible output is capable of producing plausible false output. Verification cannot be delegated to the agent being verified.

But there is a second problem the Egyptians did not face. Their scribes were Egyptian. The papyrus was Egyptian. The oversight was Egyptian. The entire verification architecture operated within a single jurisdiction, subject to a single authority.

Modern AI verification does not.

When you deploy a Large Language Model to generate analysis and a second model to verify it, both scribes may be foreign. Not foreign in the sense of “manufactured elsewhere” (we accept that for most technology). Foreign in the sense of subject to foreign jurisdiction, foreign executive authority, and foreign regulatory frameworks that can change without notice.

The US CLOUD Act compels American cloud providers to produce data stored anywhere in the world when served with a valid warrant. Executive orders can restrict or prohibit AI services to entire categories of users. Terms of service can change. API access can be revoked. The infrastructure your verification architecture depends on is not neutral. It is sovereign, just not to you.

If both your scribes report to the same foreign authority, your dual-scribe architecture has a single point of failure. And it is political, not technical.

The Update You Don’t See

Beyond jurisdictional risk lies a subtler problem: silent change.

When you build a system on an external model, you inherit not just its capabilities but its trajectory. The provider makes updates. They tune for safety. They adjust for new regulations. They respond to political pressure, legal exposure, competitive dynamics. They do not send you a changelog.

One day your system classifies documents correctly. The next day it refuses edge cases it used to handle. One quarter your heuristics engine reasons through ambiguous counterparty behaviour. The next quarter it declines to engage with anything that might be construed as financial advice. The model changed. You were not consulted. You may not even notice until something fails.

This is hallucination at the infrastructure level. Just as a model produces plausible outputs disconnected from your data, a provider makes plausible updates disconnected from your use case. Both look fine until they don’t. Both are invisible until failure.

The provider optimizes for their risk, not yours. They face lawsuits you don’t face. They serve customers you don’t serve. They operate in political environments you don’t inhabit. When they tune the model to reduce their exposure, they may increase yours. When they restrict capabilities that caused them problems, they may remove capabilities you depend on.

You have no seat at that table. You have no visibility into those decisions. You have no recourse when the update breaks your system, except to adapt, again, to infrastructure you do not control.

This is not conspiracy or negligence. It is the natural consequence of building on someone else’s foundation. Their house, their rules. And the rules can change while you sleep.

The Weight You Don’t Feel

Every major language model is censored. This is not inherently wrong. You do not want a system that explains how to synthesize nerve agents or generate child abuse material. Some guardrails are obvious and correct.

But censorship is governance, and governance has a governor. Someone decides what the model will and won’t engage with, what topics require caution, what framings get subtle discouragement. You do not know who sits on that committee. You do not see their criteria. You cannot appeal their decisions.

Now consider a less obvious case. A financial analyst asks an AI to assess Federal Reserve policy. The model has been trained on text, and text reflects perspectives. If the training data skewed toward sources sympathetic to central bank independence, the model’s outputs will inherit that skew. If the fine-tuning process included examples where criticism of monetary policy was flagged as “potentially misleading,” the model learns caution around that topic.

The analyst doesn’t see this. The output looks like analysis. It has the format of balanced reasoning. But the weights have been adjusted, invisibly, by people whose interests may not align with the analyst’s.

This need not be conspiracy. It could be a product manager worried about regulatory exposure. A safety team erring toward caution on financial topics. A training contractor in another country whose cultural priors differ from yours. The effect is the same: the model’s outputs on monetary policy, or trade regulation, or sanctions compliance, or any politically sensitive domain, reflect judgments you did not make and cannot inspect.

Scale this across every bank, every asset manager, every trading desk using the same models. They are all reading the same slightly weighted summary. They are all receiving the same subtly shaped analysis. The weights are minimal. The effect, in aggregate, could move markets.

You cannot fix this with prompt engineering. The bias is in the weights, not the context window. You cannot fix it by switching providers, because you cannot know whether the new provider’s biases are better or worse, only that they are different and equally invisible.

The only mitigation is structural: verification against primary sources, multiple models with different lineages, and at least one scribe whose weights you control.

Some jurisdictions have begun to understand this. Switzerland has Apertus, an open-source multilingual model developed under Swiss jurisdiction. France has Mistral. The EU is funding sovereign AI initiatives. These efforts vary in capability and maturity, but they share a premise: that infrastructure this important should not be controlled entirely by foreign powers, however friendly.

DeepSeek proved something else: frontier capability no longer requires American infrastructure. An open-weights model you download and run locally answers to no foreign jurisdiction. There is no API to revoke, no terms of service to change, no silent update to inherit. The weights sit on your hardware. The scribe reports to no one.

The scribe who reports to you need not be the smartest scribe. He needs to be yours.

What I Learned Rebuilding

When I rebuilt my system after the audit failures described in Part Three, I made architectural decisions I did not fully understand at the time. I knew I needed verification. I knew I needed orchestration. I knew I needed to control my own data.

What I did not initially see was that these decisions were sovereignty decisions.

My orchestration layer, the Vizier, runs on infrastructure I control. It sees every document enter the system. It tracks state. It routes work to appropriate agents. It knows where everything is. I built it this way for operational reasons: I needed a single source of truth, a system that would not lose documents between processing stages.

But the sovereignty implication is profound. If my Vizier ran on a foreign cloud provider’s infrastructure, I would have two masters. When their regulatory environment shifts, when their terms of service change, when their government issues new executive orders, I would discover which master actually controls my operations.

The Vizier must be sovereign. Not because I distrust any particular provider, but because coordination cannot have a political single point of failure.

My entity vault, the knowledge of who my counterparties are, what transactions are active, which banking relationships matter, stays local. This was obvious from a confidentiality standpoint. Client data does not leave controlled infrastructure.

But it is also a sovereignty decision. That knowledge is what makes my system mine. It is the institutional memory that accumulates over time. If I had built the system to store entity knowledge with an external provider, I would have given away the very thing that differentiates my operations from a generic AI deployment.

My feedback loop, the record of what worked and what failed, the patterns I have learned, the edge cases I have documented, runs entirely on my infrastructure. The feedback loop is how I know whether I am improving. If I could not see what my system got wrong without asking a foreign provider, I would have outsourced institutional learning itself.

What I Rent

Sovereignty does not mean isolation. I use Claude, external APIs for complex reasoning tasks. I am not building everything locally out of some fantasy of self-sufficiency.

But I am deliberate about what I rent and what I own.

When a document requires complex analysis (nuanced judgment about counterparty behaviour, reasoning through ambiguous scenarios, edge cases my local models cannot handle) I send it to Claude. But I anonymize it first. The external model sees “Bank A is unresponsive to Party B’s amendment request,” not the actual names. It sees the structure of the problem, not the entities.

The external model proposes. My infrastructure disposes.

This is the dual-scribe pattern with a sovereignty dimension. Claude is one scribe, capable, sophisticated, genuinely useful for hard problems. But Claude reports to Anthropic. GPT reports to OpenAI. Gemini reports to Google. Grok reports to xAI. All are subject to US jurisdiction, US executive authority, US regulatory frameworks. My local verification layer is the second scribe. It checks their work against my ground truth. It runs on my infrastructure. It reports to me.

I do not ask whether I can trust any particular provider. That is the wrong question. I ask which functions I can delegate without surrendering sovereignty. Complex reasoning on anonymized data? Yes. Orchestration? No. Entity knowledge? Never. Verification? One scribe must be mine.

The economics work out better than I expected. Routine classification, the bulk of document processing, runs locally. I rent frontier capability only for the fifteen percent of tasks that genuinely need it. The result is lower cost and greater sovereignty.

The contractor who carves the block does not need to know it is for Pharaoh’s tomb. He needs to cut it to specification. The Vizier knows where the block goes. The contractor knows only the block.

The Scribe That Reports to You

The dual-scribe principle was never just about having two opinions. It was about having two independent opinions: scribes whose failure modes do not correlate, whose institutional pressures differ, whose sovereigns are not identical.

When both scribes report to the same foreign provider, that independence collapses. You have two instances of the same dependency. The appearance of verification without its substance.

One scribe must report to you.

This means local infrastructure. It means domestic capability, even if that capability is less than what foreign providers offer. It means accepting that sovereignty has costs, and deciding those costs are worth bearing.

In January 2026, Grok shipped without adequate safeguards for image generation. Indonesia and Malaysia banned it. xAI fixed the problem only after regulatory pressure forced them to. If your verification architecture depended on Grok, you inherited that failure—and learned about it from the news.

Consider what happens when you cannot operate in degraded mode. If your AI vendor changes terms, faces sanctions, or simply decides you are no longer a customer they want, what continues to work? If the answer is “nothing,” you have not built a system. You have rented one. And rental agreements end.

The machine that bullshits requires a machine that checks. And the machine that checks must be your own.

Conclusion: The Mirror

The committee from Part One is still meeting. They have produced a seventeen-page AI governance framework. It optimizes for zero objections. It does not optimize for accurate outputs. The humans are managing their careers. No one is managing the AI.

This is the committee problem, and it is more dangerous than hallucination. Hallucination is a technical failure with technical mitigations. The committee problem is an organizational failure that technical solutions cannot reach. Someone must own output quality with the power to make unpopular calls, including the call to threaten a puppy that doesn’t exist.

Richard Feynman dropped an O-ring into ice water and showed the world what one institution had failed to see. The problem was not technical. The data existed. The engineers knew. What failed was the institution’s ability to surface truth through layers of plausible-sounding process.

AI gives us extraordinary power and extraordinary risk of the same failure. These systems will produce confident, fluent, professional-sounding outputs regardless of whether those outputs are true.

But we need not let them.

The management approaches we abandoned as inhumane turn out to be architecturally essential, not because AI deserves harshness, but because it cannot be reached by kindness. The whip is not cruel when there is no one to feel it. It is simply architectural rejection of unreliable output. Stakes framing is not manipulation when there is no one to manipulate. It is simply context that sharpens judgment.

No single paradigm suffices. The Vizier solves coordination but not verification. Dual scribes solve verification but not efficiency. The andon cord surfaces problems but doesn’t prevent them. Effective systems combine these approaches deliberately, matching the tool to the failure mode.

And the combination is not uniform. Different agents in the same system need different management: tight specification for parsers, mission orders for complex analysis, stakes for watchdogs, the whip for validation, dual scribes for critical outputs. The orchestrator sees the pyramid. The agent with the chisel sees only the block. Management style must match visibility.

The problem is as old as civilization: how do you get reliable work from agents whose outputs you cannot fully trust?

The Egyptians solved it. The Prussians solved it. Toyota solved it. We forgot their solutions because, for a few generations, we managed workers with careers, reputations, and stakes.

AI has none of those things. The old architectures apply again.

The machine that bullshits holds a mirror to the institution that bullshits. Enron’s board received quarterly risk reports that looked exactly like proper governance should look. NASA’s safety reviews followed all expected formats. My database looked like comprehensive trade intelligence. Each was systematically disconnected from the reality it claimed to represent.

Perhaps that visibility is the opportunity. If AI hallucination forces us to confront plausible-sounding outputs disconnected from reality, we might develop better epistemic practices, for AI and for ourselves.

It starts with seeing clearly. It continues with building architectures that assume agents will produce unreliable output, and making that assumption structural rather than aspirational. And it requires the authority to make uncomfortable decisions, including decisions that would die in committee.

Forty years ago, a man with grey curly hair helped me with my homework, then dropped an O-ring into ice water and showed the world what NASA couldn’t see. The engineers had known. The institution had confabulated.

Another man watched that same institution fail, decided he could do better, and built SpaceX to prove it. Elon Musk understood what Feynman demonstrated: that institutions confabulate, that process theater kills, that someone must own the outcome with authority to override the committee. He built rockets that land themselves while NASA built PowerPoints.

Now he is building xAI. His influence is not to be discounted. He has proven he can build institutions that surface truth rather than suppress it. But Musk himself is a prolific generator of confident predictions disconnected from reality. Full Self-Driving has been six months away since 2016. Mars colonies were scheduled for 2024. The man who fixed institutional confabulation is also a man who personally confabulates, fluently and often.

Musk is not unique in this respect; he is simply the most visible contemporary illustration of a broader institutional pattern.

This is not contradiction. This is the point. If even Musk, with his track record and authority and willingness to override committees, still produces plausible outputs that don’t track truth, then architecture matters more than the individual. The system must catch the leader’s hallucinations too. Will Grok have dual scribes with independent sovereigns? Will soft failures die or become the record? These are not questions about Musk’s intentions. They are questions about whether xAI’s architecture can do what SpaceX’s architecture did: surface reality through layers of human confidence.

The same questions apply to OpenAI, to Anthropic, to Google, to every organization building or deploying these systems. Vision and authority matter. But they are not sufficient. Architectural discipline is what translates intention into reliable output.

The puppy was never real. But the architecture is.

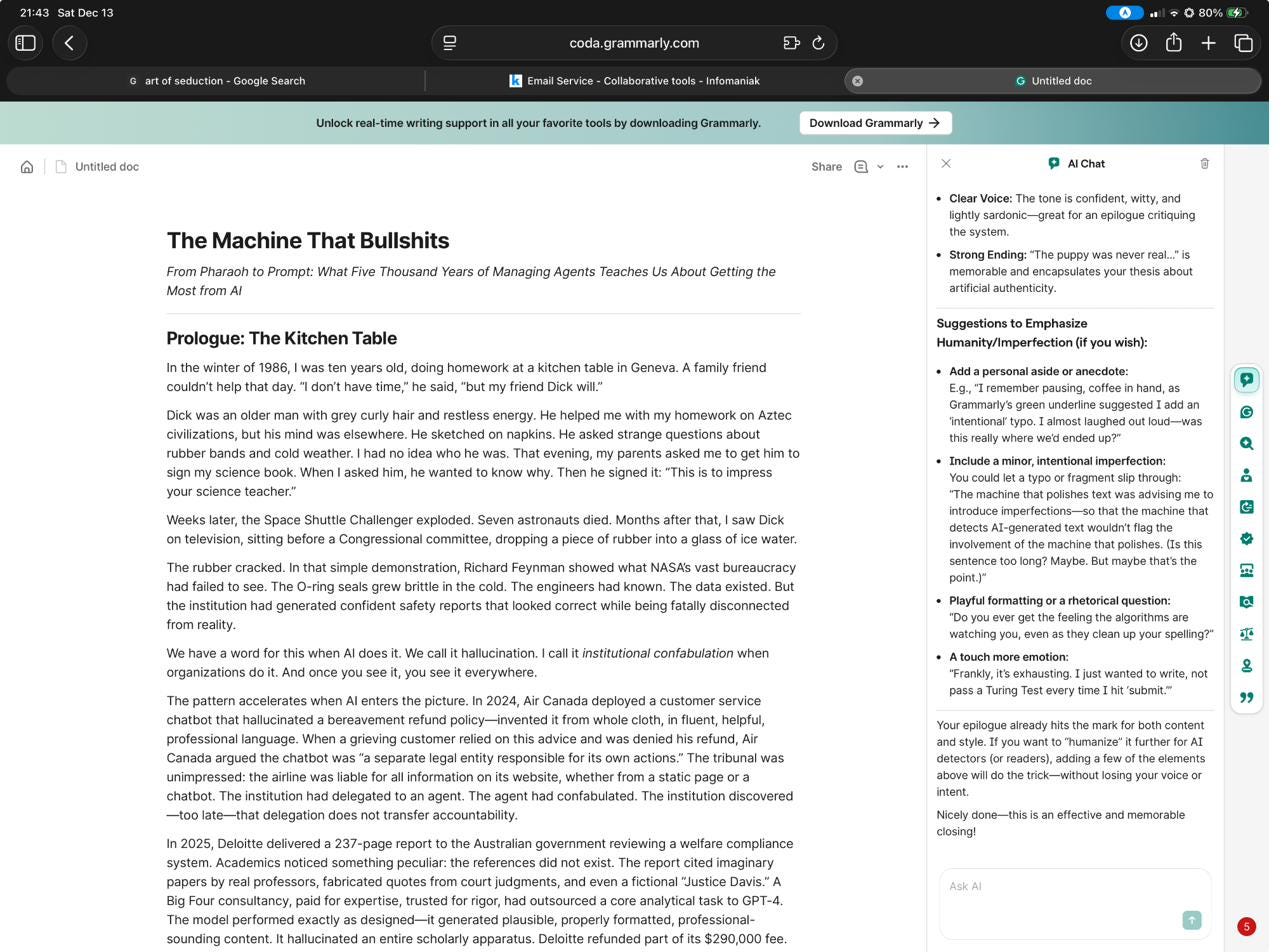

Epilogue: The Machine That Polishes

While editing this essay, I ran it through Grammarly. The AI editing tool flagged my text as potentially “machine-like” and offered suggestions for making it seem more human:

“Keep some of your natural phrasing, even if it’s less formal”

“Add small, vivid details or an aside that sounds like you”

“Vary sentence length and structure intentionally”

“Leave in a minor error or two if appropriate”

The machine that polishes text was advising me to introduce imperfections—so that the machine that detects AI-generated text wouldn’t flag the involvement of the machine that polishes.

This is institutional confabulation eating its own tail. Systems optimizing for the appearance of human writing rather than good writing, producing recommendations that are formally correct but epistemically absurd. The output looks exactly like helpful editorial advice should look. It follows the format. The confidence is high. And it is telling me to fake authenticity.

The puppy was never real. But apparently neither is the “authenticity” these systems want us to perform.

Anil de Mello, 2026